Okadaya Fuse

Drum

“Crafted to Last a Lifetime”

Here, they are made entirely in Japan, using only domestically sourced materials and crafted by Japanese artisans’ hands—this is something we do not compromise on.

About

We regard wadaiko—Japanese drums—as among Japan’s most deeply rooted traditional instruments, still in use today. Here, they are made entirely in Japan, using only domestically sourced materials and crafted by Japanese artisans’ hands—this is something we do not compromise on.

Both wadaiko and omikoshi (portable shrines) are produced from the ground up. Beyond omikoshi, we also work with festival implements used in local rites. Beyond wadaiko, we also work with narimono—traditional Japanese sound-making instruments such as tsuzumi hand drums and other percussion used in Japanese music. Ritual items such as Buddhist altars and Shinto household shrines are also handled as part of this work.

Origins

The business was founded in 1835, in the late Edo period—nearly 190 years ago. Since then, we have continued in the same place, maintaining a steady presence through changing times.

In those days, wadaiko were far more familiar and widely used than they are today. Asakusa had long flourished as a lively entertainment district, with kabuki theaters, geisha performances, and rows of playhouses. Across these settings, the sound of drums was always present—in moments of celebration, performance, and gathering. In a town shaped by such scenes, Asakusa naturally became a place where demand for drums emerged. At the time of the founding, tools related to music were readily available here, and we understand that the work extended beyond drums to a wide range of instruments.

Relationship with Asakusa

Every May, Asakusa hosts the Sanja Matsuri, one of Tokyo’s largest annual festivals and a central event in the life of the area. During the festival, deities are enshrined in omikoshi (portable shrines) and carried through the town.

While often translated as “festival,” a Japanese matsuri is rooted in the act of worship. At its heart is the moment when the deity leaves the shrine once a year to meet the people who live in the community. For many Japanese, the omikoshi is therefore not simply ceremonial, but a deeply meaningful presence.

Wadaiko are also central to these occasions—played on festival floats, in ohayashi ensemble music, and during bon-odori dances. In a town shaped by such traditions, being able to make both omikoshi and wadaiko here in Asakusa is something we feel deeply grateful for.

Materials

Wadaiko are made from two essential materials: zelkova wood (keyaki) and cowhide

Zelkova is valued for its hardness, which allows sound to resonate clearly while providing the durability needed for long-term use. From raw timber to a stage ready for making the drum body, the wood requires a drying period of five to ten years. Zelkova trees naturally grow in irregular forms, and shaping a full-sized drum body therefore requires timber of exceptional diameter. Today, trees of this size have become increasingly difficult to obtain, making zelkova both scarce and steadily rising in value.

For the drumheads, cowhide from aka-ushi—Japanese cattle with brown coats and naturally low fat content—is used. The hide is tanned and then dehaired and used as it is; if excess fat remains, the leather can deteriorate more easily over time. For this reason, the lean hide of aka-ushi is particularly well suited to wadaiko. Among wagyu cattle, aka-ushi account for only about five percent of total domestic production, making this material especially scarce.

Process

We continue to follow traditional methods throughout every stage of production.

For example, surfaces are finished by hand using kanna (Japanese hand planes). The results differ entirely from machine cutting: planing by hand allows the wood to be shaped evenly and finished with greater precision and clarity.

The same approach applies to finishing. We do not use polyurethane coatings, instead applying natural varnish—the same type traditionally used on violins. Varnish can be layered and restored over time, allowing the surface to be repaired and refined even after damage. With polyurethane, once the surface is scratched, it cannot truly be repaired; reapplying the coating rarely removes the mark.

Because wadaiko are instruments meant to be repaired repeatedly and used across generations, we place great importance on making them in ways that allow this to happen. For that reason, we continue to value traditional processes and materials, including our choice of finishes.

Design

Archaeological findings suggest that objects shaped like wadaiko have been unearthed from ancient burial mounds dating back more than a thousand years, including clay figures and pottery made in forms nearly identical to those seen today. If the basic form was already established at such an early stage, it is thought that drums themselves may have existed even earlier. Some scholars suggest that by the Jōmon period—several thousand years ago—a prototype of the wadaiko may already have taken shape. Over an immense span of time, this form has been passed down with remarkably little change.

Seen this way, the continuity of the wadaiko’s design feels almost extraordinary. It may be that the form is rooted deeply in human senses and daily life—something fundamentally universal, and therefore unchanged.

WORKS

Our values

Yoshihiro Fuse

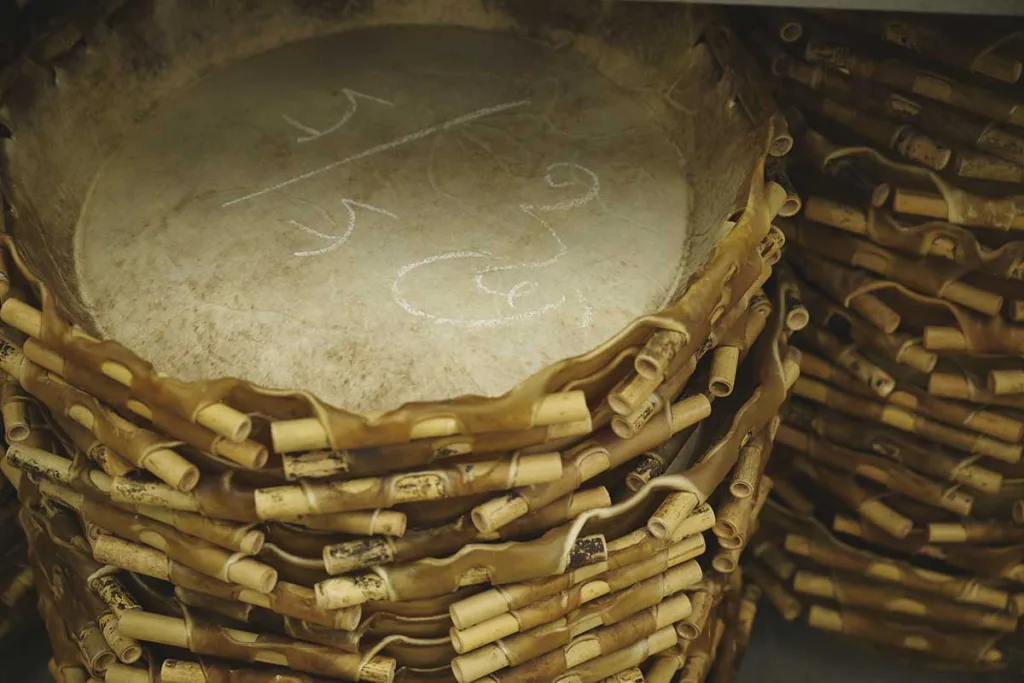

When a drum is reheaded, the name of the artisan who originally made it is written inside the body. We may never meet that person, or know who they were, yet we are touching the same drum they once worked on. With that awareness, we think about how the drum will be treated at its next repair, and how it will continue its journey over time. As years pass, some workshops and artisans disappear, and their names fade from record. For us, preserving names—and the record of those who worked on each piece—is deeply important. In this way, the work is carried forward to the next generation.

Few objects are meant to be repaired and used across generations in the way wadaiko are. Being able to work with them is something we feel deeply grateful for. That awareness returns each time we look inside a drum and see the names written there. It reminds us of our responsibility—to do our work properly, and to continue making each piece with care.