Oshimaya Onda

Chouchin

“Even Without a Candle, Radiates Warmth”

Chōchin are traditional Japanese lanterns that were originally used as lighting devices powered by candle flames. They illuminated paths at night, and functioned as signboards for shops and eateries.

About

Chōchin are traditional Japanese lanterns that were originally used as lighting devices powered by candle flames. They illuminated paths at night, served as landmarks at shrines and temples, and functioned as signboards for shops and eateries.

Chōchin are made with washi paper, which has long been believed to absorb negative energy. The lantern’s body—called the hibukuro—is made in an accordion-like structure, allowing it to be folded. The accordion-like form is called jabara. There are various interpretations of the word’s origin, but it has long been associated with harau, or warding off negative energy—linked by sound to ja (negative) and bara (to dispel). For this reason, jabara has traditionally been understood as carrying an auspicious meaning. When a place is purified and good energy circulates, good people naturally gather. Such auspicious beliefs are also embedded in the chōchin.

Origins

Chōchin are said to date back to the late 16th century. At that time, they did not yet have the foldable jabara form seen today. Instead, early lanterns were known as kago-chōchin, made by weaving thin bamboo strips into a basket-like frame and covering it with washi paper.

As demand grew during the Edo period, beginning in the early 17th century, chōchin gradually evolved into the form seen today. Rather than leaving them fully extended at all times, it became practical to fold them during the day and open the hibukuro at night when in use. This led to the development of the foldable jabara structure.

Because chōchin originally used candlelight as their source of illumination, their role as everyday lighting gradually declined with the spread of electric light from the Meiji period onward. Even so, they continued to be used as shop signs, in festivals, and for celebratory occasions. While their purposes may have shifted slightly over time, the way chōchin are used has remained fundamentally unchanged.

Relationship with Asakusa

Asakusa is often closely associated with chōchin, largely because of the iconic giant lantern at Kaminarimon Gate. During festivals, tall takahari chōchin, bow-shaped yumihari chōchin, and lanterns bearing the names of individual neighborhoods are hung throughout the area. These lanterns have long formed part of the everyday scenery of Asakusa.

In the past, Asakusa was home to many theaters, including kabuki playhouses. Rows of chōchin lining their entrances remain an enduring image of the area.

From the Edo period onward, chōchin making developed through a system of specialization. The work of pasting the paper hibukuro was carried out in the Mito area of present-day Ibaraki Prefecture, while lettering and finishing were done in Edo, Tokyo. Asakusa, located along the main routes connecting Edo to the north, was well positioned within this network.

By making use of regional strengths and dividing roles among skilled artisans, chōchin culture took root in Asakusa. In that sense, the close relationship between Asakusa and lanterns was not accidental, but a natural result of geography, craftsmanship, and the rhythms of the city itself.

Materials

The basic structure of chōchin has remained unchanged. They are made using 100% kōzo washi paper. The ribs are formed from finely split bamboo, carefully shaved into slender strips. The kuchiwa—the top and bottom rings—are made of wood. Vertical threads and natural adhesives are also essential components. In the past, paste was made from rice, and similar methods are still remembered today.

It is true that not all materials can be sourced in exactly the same way as before. Craftspeople who produce these materials are becoming increasingly rare, and some aspects have inevitably changed over time. Even so, finding ways to adapt while ensuring that chōchin continue into the future is essential. Losing what once felt ordinary would be a great loss.

Process

Our role has traditionally been to hand-paint the lettering on chōchin.

In reality, chōchin making is almost entirely a collaborative craft. The hibukuro is made by specialists; the internal components are produced by others; the top and bottom frames are crafted elsewhere. Each lantern brings together the work of many hands, and each role requires its own successor.

This division of labor developed largely because Edo was a densely populated city. Chōchin were daily necessities, used as lighting before electricity. Demand was so high that no single workshop could handle every step alone.

What is remarkable is that, although each part is made by different hands, everything comes together seamlessly in the end.

The harmony—the way separate work unites into a single lantern—is something we find genuinely appealing.

Design

The lettering we paint belongs to a style of Edo calligraphy known as chōchin-moji. It is based on brush-written block characters, thickened and emphasized so they remain legible from a distance. Strokes such as stops, sweeps, and flicks are intentionally accentuated.

Because chōchin surfaces are uneven due to the bamboo ribs, writing directly with a single stroke would cause ink to pool and run. To prevent this, we first outline the character and then fill it in—a technique known as kagoji.

Although digital fonts sometimes imitate this style, true kagoji exists only through handwork. There is no single “final” form. While there are foundations, we believe the writing continues to evolve throughout one’s life. Mastery is never complete.

WORKS

Our values

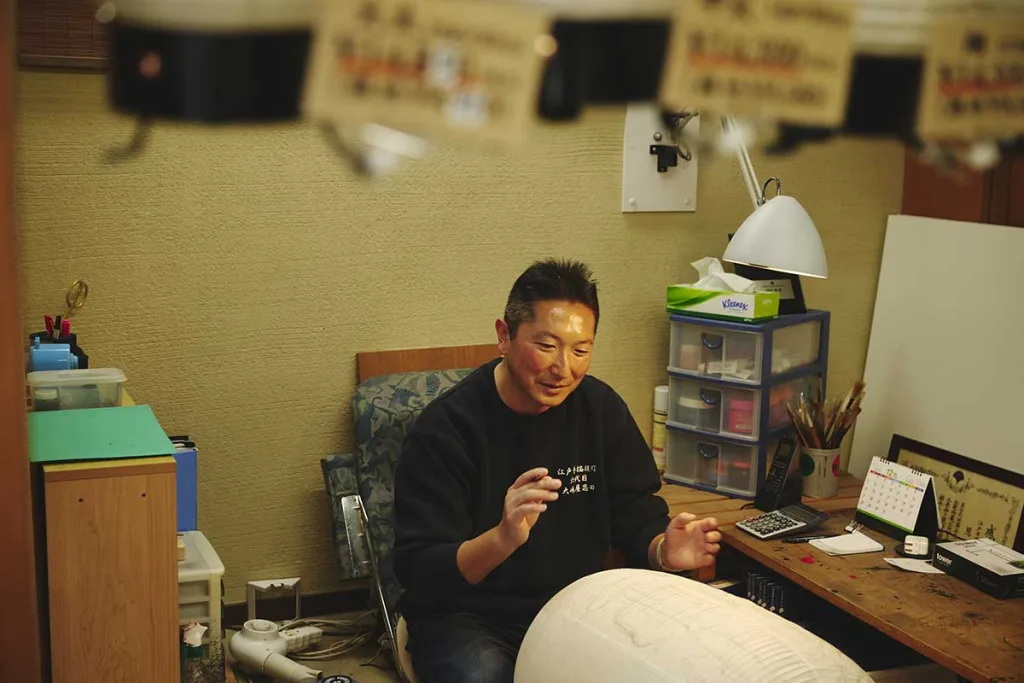

Osamu Onda

What we value most is continuity—ensuring that chōchin are not lost, but passed on.

We are grateful that people from overseas have also begun to take interest. We listen to their stories, paint the lettering, finish each piece, and hand it over. When all those intentions come together, the chōchin itself already carries warmth. Even without a candle, a chōchin feels warm, filled with the care and intentions of those who made it.

Of course, when a candle flame is lit inside, the light diffuses softly through the washi paper. The glow spreads gently, lifting the mood and drawing attention—especially at night. That is why chōchin have always been so well suited to shops and gathering places.

A candle flame is surprisingly bright. It is different from battery-powered light. Fire is, by nature, the enemy of washi—yet a living flame is placed inside it. That slight tension, that sense of risk, is also part of the appeal. Because it is fragile, it is treated with care. And perhaps that care is what makes a chōchin feel warm, even before the flame is lit. When you sense that, you naturally want to take good care of it.